| Login | ||

Healthcare Training Institute - Quality Education since 1979

CE for Psychologist, Social Worker, Counselor, & MFT!!

Section 13

Defensive Aggression

Question 13 | Test | Table of Contents

During treatment you have to deal with the guilt, shame, fear, and pain that you feel for yourself and for others. You may be using your defense mechanisms to avoid these feelings. However, in order to manage your anger better, you have to come to terms with these feelings. The first step is to recognize that you are using defense mechanisms. Listed below are six types of defense mechanisms. Do you recognize any of them in yourself?

1. Rationalizing. Rationalizing is making excuses and justifying your behavior, even though you know that what you are doing is wrong. Examples: "I wasn’t doing anything wrong. I was just teaching her about sex. I have a right to get angry when I’m under a lot of stress."

2. Intellectualizing. When you intellectualize, you avoid dealing with the inner truth about your feelings. You make theories, but they don’t make any deep connection to you or your behavior. You may say some of the right words about anger, or about offending behaviors, but it is always about other people's anger. In an attempt to avoid personal responsibility and change, you might say, "Oh, yes, I understand. The majority of expressed anger causes fear in the recipient." If you were not intellectualizing, if you were being honest about your feelings, you might say, "Oh, I understand. When I scream and yell at my wife and shove her against the wall, I’m terrorizing her. I’m bigger and stronger than she is and it isn’t fair. But when I’m angry, I want her to be scared because that's the only way she’ll do it my way and stop contradicting me. When she contradicts me, I feel disrespected as a man." When you are intellectualizing, you hide your feelings behind generalizations or "research" (things you may have read that, taken out of context, tend to support your denial). An example: "Research shows that it is healthy to express anger as soon as it is felt." Someone may have written that, but the author was talking about the nonabusive expression of anger, not breaking furniture or threatening people.

3. Denial. When you deny, you refuse to admit the truth about your problems even though you know that it’s true. You simply lie to yourself and others. You don’t want to admit to yourself or others that you really did what you did, so you pretend that it didn’t happen or that you weren’t involved. There are different kinds of denial:

Responsibility. Denying responsibility is saying that you had nothing to do with the fight, the injury, the property damage, or any crime for which you may have been convicted. You deny any wrongdoing. Examples: "I didn’t rape her. It wasn’t me who broke the window. I didn’t start the fight. I don’t know what you’re talking about."

Intent. Denying intent is admitting to doing the offensive behavior but denying that you did it on purpose. You are saying that you did not intend to do the offense, that it just "happened," or that it was an accident, so therefore it is not your fault and you are not responsible. Examples: "I didn’t mean to do it. I don’t know how it happened. All I did was duck—it’s not my fault the bottle missed me and went through the window."

Harm. Denying harm is claiming that what you did to the victim of your anger caused no "real" harm. Most men with anger problems deny they’ve caused harm because no arms or legs were broken, no bodily harm is visible. They ignore that sexual, verbal, and physical assaults cause mental and emotional harm that is sometimes more damaging than bruises or broken bones. They can’t connect with how the other person might have felt. They don’t have empathy. Examples of statements denying harm: "He didn’t get hurt. The beer bottle I threw hit the wall, not the kid. She’s faking to get sympathy. I only punched the bed next to her head."

Frequency. Denying frequency is saying that the assaults didn’t happen as often as the victim reports they occurred. Examples: "I only hit her once. I’ve only got into a couple of fights."

Intrusiveness. Denying the level of intrusiveness is stating that what you did was not as disturbing, invasive, or hurtful as the victim reports that it was. Examples: "Her blouse tore a little—I didn’t rip it off. I pushed the door open—I didn’t break it down."

Premeditation. This form of denial is claiming that you did not plan your crime or assault. It is denying that any thought went into what you did before you did it. Examples: "It just happened. I didn’t plan it."

Minimization. When you minimize your behavior, you try to make it seem less serious than it really is. You downplay and understate the truth about a situation. For example, you might claim "I only took her for a ride," when discussing a kidnapping, or "We just had sex," when talking about rape. Examples: "I only called her names—I didn’t hit her. He’s making a mountain out of a mole hill."

4. Religiosity. Many men with anger problems "see the light" and become super-religious after they seriously hurt someone they care about or after they are arrested for a violent episode. Practicing a religion can be a positive influence. We encourage you to develop the spiritual side of yourself. True spirituality supports your being responsible in your life. Religiosity, however, is different from spirituality and positive religious practice. It is often used as a defense mechanism, a way of using religion to avoid being responsible. Some people with anger problems make their religion an excuse not to involve themselves in treatment. They say, for example, "I don’t need treatment, I’ve been forgiven." Elton, who had been arrested for several assaults, at one time said, "I do not need treatment because God has forgiven me and is healing me of my anger." He was hiding from his need to take responsibility for changing himself by using religiosity.

On the other hand, your sincere involvement in a religious practice can help you come to terms with your problems and may even help you make positive changes. But it cannot and should not be used as an excuse to avoid dealing with your past or present problems. Religion is not a shield to fend off dealing with real-life issues.

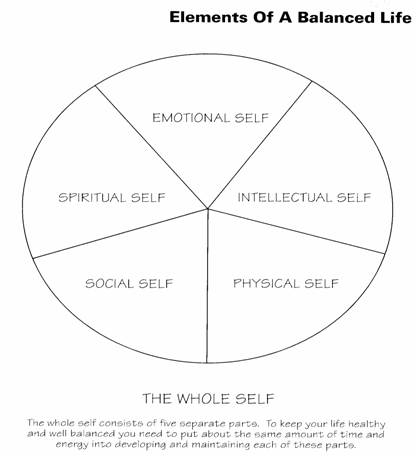

One last word on spirituality. One of the important tasks in maintaining a healthy lifestyle is to keep your life balanced. Imagine your life as a circle with five equal segments like a pie (see Figure 5). The pieces of your life are your Spiritual Self, Physical Self, Social Self, Thinking Self, and Feeling Self.

Each part of your self should be equal to every other part in order to for you to lead a healthy, balanced life. If any one part gets too large, your life becomes out of balance, like a wheel with a bulge in it. If you focus too much on religion, that part of your self gets larger and other parts of your self get smaller. Religion becomes an end in itself rather than a way to express your spirituality, and it turns into religiosity. When you ignore one part of your self to work on another there is usually a negative impact in the long run.

5. Justification. When you justify your behavior you make excuses for it, defend it, or explain it away. You do not take responsibility for what you do. For example: "I can’t control my anger— it’s hereditary, my father is the same way."

6. Blame. People with anger problems often blame others for their anger. It is a way to not be responsible for what you do. For example, you hit someone and then blame the other person by saying, "He was looking for trouble."

Men with anger problems usually have a hard time with three issues: taking full responsibility for any violent or criminal behavior, letting go of their defense mechanisms, and managing their anger. Angry people have problems with their defense mechanisms getting in the way of dealing positively with their anger. Very angry people use their defense mechanisms so much that they don’t even realize that they have them.

Your defense mechanisms are barriers you use to block yourself from being really involved in your anger management program. The good news is you can learn to overcome them. Your defensiveness does not have to be a big hurdle to making positive changes in your life. If you can say out loud to your treatment group, counselor, or friends that you use defense mechanisms and notice which defense mechanisms you use, you’ve made a big step toward managing your anger in nonhurtful ways. Once you can let down your defenses and keep an open mind about making changes in your life, then you can deal with the real issues of why you act out your anger violently.

Cullen, M., & Freeman-Longo, R. (1995). Men & Anger: A Relapse Prevention Guide to Understanding and Managing Your Anger. Safer Society Press.

Personal

Reflection Exercise #6

The preceding section contained information

about recognizing defense mechanisms. Write

three case study examples regarding how you might use the content of this section

in your practice.

Reviewed 2023

Update

Aggression, Aggression-Related Psychopathologies and Their Models

Haller J. (2022). Aggression, Aggression-Related Psychopathologies and Their Models. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience, 16, 936105. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2022.936105

Peer-Reviewed Journal Article References:

Casini, E., Glemser, C., Premoli, M., Preti, E., & Richetin, J. (2021). The mediating role of emotion regulation strategies on the association between rejection sensitivity, aggression, withdrawal, and prosociality. Emotion. Advance online publication.

Halevy, N. (2017). Preemptive strikes: Fear, hope, and defensive aggression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 112(2), 224–237.

Park, Y. C., & Pyszczynski, T. (2019). Reducing defensive responses to thoughts of death: Meditation, mindfulness, and Buddhism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 116(1), 101–118.

Volk, A. A., Andrews, N. C. Z., & Dane, A. V. (2021). Balance of power and adolescent aggression. Psychology of Violence. Advance online publication.

QUESTION 13

What are the five elements of a balanced life? To select and enter your answer go to Test.